Building Super Fast Web Apps with PJAX

There has been a great deal of interest recently in client side frameworks such as Knockout.js, Backbone.js, and Ember.js. These frameworks are great, but sometimes they are either overkill or simply too complicated for your particular purpose. Traditionally, the alternative approach was to just use a pure server-side framework like Ruby on Rails or ASP.NET to build HTML and serve it to your users. However, there is a third approach that, while not new, has peeked my interest recently. This approach has been nicknamed PJAX. PJAX is a blend between client side and server side rendering of HTML.

The basic idea of PJAX is that you update only the parts of the page that change when the user navigates through your app. However, unlike a normal AJAX app that returns only data (JSON) from the server, a PJAX request actually contains normal HTML that has been generated on the server. This HTML is only a fragment of the full page and using Javascript on the client this fragment is substituted in for the last page’s content.

Below you see a diagram of how this works.

The first request to the server is a normal request (1). The server then returns the page in the normal fashion (2). The difference with PJAX is with subsequent requests. For example, if a user clicks on a link that opens the /about page the client-side JavaScript makes a request for only the parts of the page that need to change (3). The server then generates the html of the only the changed content and returns it in the response (4). The client-side JavaScript then replaces the old content with the new content.

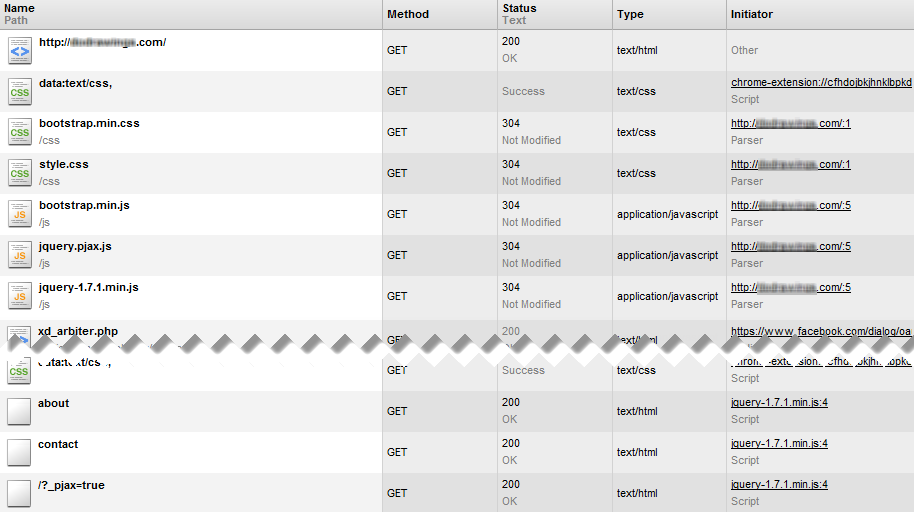

You can see in the next image how the network traffic of the requests look. The first page is loaded along with all the supporting static content. You can see at the bottom the requests for the ‘about’ and ‘contact’ pages. When the user navigates to these pages, only the new content is requested from the server; in these cases partial HTML pages. You can see this technique results in far fewer HTTP requests to the server and less content being sent over the wire. This reduces the load time of the page and will also reduce load on your server and bandwidth usage.

This technique has been implimented in a variety of ways. You may recall that ASP.NET actually ships with something like this called partials. The method I am using is a bit more do-it-yourself, but it is similar. So lets take a look at how this could be implimented using Node.js with Express.

On the client I am using a great jQuery library called jQuery-pjax. This library takes care of some of the lower-level code such as making the ajax request and replacing HTML content. By using this library you can impliment the pjax request with only a few lines of code.

The first thing we need to do is setup our links to be pjax links. We can do this by adding the data-pjax attribute to the link. This attribute is set to the container where the content will be loaded. In this case a div with the id set to ‘main’.

<a href='/explore' data-pjax='#main'>Explore</a>

Next, we simply need to call the pjax extension on every element that contains the data attribute ‘data-pjax’. You can see how we do this in a single line of code below.

$('a[data-pjax]').pjax()

That’s it for the client; now we need to modify the server. The trick with this library is that when a PJAX request is made an HTTP header named ‘X-PJAX’ is added to the request. By looking for this request our server knows whether to return only the html fragment that applies to this specific content or to return the entire HTML document.

There is a node module called express-pjax that extends Express and actually takes care of handling these PJAX request for us. This module is very simple. All it does is look for the header and if the header is present it sets the request options to not use a layout page. This results in only the portion of our view that is page specific to be rendered and returned. If the PJAX header is not present then the page is rendered like normal with the full view. The code of this module is below.

module.exports = function() {

return function(req, res, next) {

if (req.header('X-PJAX')) {

req.pjax = true;

}

res.renderPjax = function(view, options, fn) {

if (req.pjax) {

if (options) {

options.layout = false;

} else {

options = {};

options.layout = false;

}

}

res.render(view, options, fn);

};

next();

};

};

Since we are using the express-pjax module we only need to make a simple modification to our routes. Instead of calling render we need to call renderPjax.

module.exports = function(app) {

app.get('/', function(req, res) {

res.renderPjax('home/index', { title: 'SocialDrawing' });

});

app.get('/about', function(req, res) {

res.renderPjax('home/about', { title: 'About' });

});

app.get('/contact', function(req, res) {

res.renderPjax('home/contact', { title: 'Contact' });

});

};

The beautify of this method is that it requires very little change to your application and you can share url routes with both the client and the server. Additionally, because jQuery-pjax uses the HTML5 history API you don’t have to use hashes in your urls. Lastly, any browser that is not compatible with this approach will just revert to normal requests which means you can support every browser back to IE6 (not that I recommend doing that).

Events

A common issue with this method is executing Javascript when a PJAX page is loaded or unloaded. To handle this the jQuery-pjax library has a number of events you can subscribe.

$('a.pjax').pjax('#main')

$('#main')

.on('pjax:start', function() { $('#loading').show() })

.on('pjax:end', function() { $('#loading').hide() })

By subscribing to these events you can run code that you would normally run on $(document).ready(). In a future post I will show you how you can use these events to automatically handle loading and unloading views in a way that also works with normal page loads.

Caching

In order to further improve the performance of you PJAX page loads you should impliment server-side and client-side caching. By utilizing caching you can build an application that is extremely responsive and in most cases your uses will not be able to tell the difference between this style of application and a full client-side application. There is a great article written on the 37Signals’ blog about how they used this approach in their new version of Basecamp. The post goes into detail about how they use PJAX and caching to build a super fast app.

Conclusion

The biggest advantage of this approach is simplicity. I find that writing an application in a full client-side framework can result in a great app, but sometimes it is overly complicated. With great server-side tooling available for rendering views in frameworks like ExpressJS or ASP.NET MVC sometimes it is just easier to handle the view rendering on the server. The PJAX approach allows you to use the tools you are familiar with while still getting great client-side performance. As with most design choices, there are trade-offs. This approach isn’t for every app, but it is a great tool to have available and use when appropriate.